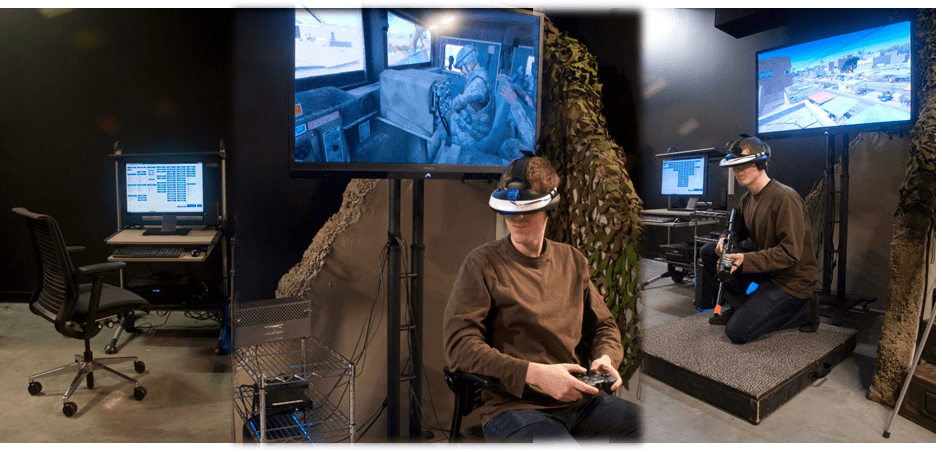

Psychologist Albert “Skip” Rizzo conducts research on the design, development, and evaluation of virtual reality (VR) systems targeting the areas of clinical assessment, treatment, rehabilitation, and resilience. This work spans the domains of psychological, cognitive and motor functioning in both healthy and clinical populations. Rizzo, whose work using VR-based exposure therapy to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) received the American Psychological Association’s 2010 Award for Outstanding Contributions to the Treatment of Trauma, is the director for medical virtual reality at the University of Southern California (USC) Institute for Creative Technologies. He also holds research professor appointments with the USC Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and at the USC Davis School of Gerontology.

How would you say that mixed reality differs from virtual and augmented realities?

Skip Rizzo: I look at virtual, augmented and mixed reality as different tools in a toolbox—sometimes you need a hammer, sometimes you need a screwdriver, sometimes you need a wrench. It’s not so much about it being a horse race; it’s about finding the proper tool for the needs of a specific application. With mixed reality, I think we get the best of both worlds—the integration of digital- and physical-world properties—and that allows us to create compelling applications, particularly in my area, which is healthcare.

How do these technologies relate to your work?

The whole purpose of using these technologies in rehabilitation is very simple—it’s a motivator. They motivate people who oftentimes have physical impairments due to their neurological condition. For them to do rehab with traditional tools, whether it’s blocks or objects that they have to pass from hand to hand or reach for, it’s very, very boring and very frustrating because they’re seeing constantly where they’ve lost function. Anything we can do to gamify rehabilitation, to take the onus off of the loss and refocus more on the compelling properties of game-like content, is a good thing to do.

These are very boring mundane tasks that we do every day and don’t even think about, but, after you’ve had some kind of a physically disabling health condition, these are the challenges of just maintaining your functional ability. We’ve got to come up with a way to illustrate these mundane activities in the rehab process for helping people to reacquire functional skills; by doing it in a mixed reality context, we can add in motivators. Maybe an artificially intelligent virtual human representation of a rehab counselor appears in the mixed reality world and gives the patient a pep talk. The software is monitoring the person’s hand position and movement and giving advice throughout the activity. It’s creating a way that somebody can stay motivated to do rehab on a daily basis, even when the living, breathing, flesh-and-blood physical therapist isn’t there.

Or, imagine your grandmother having dementia. She can still basically operate independently in her home, but she needs a caregiver at times. What if when your grandmother puts on these augmented reality glasses, she has a virtual human support agent that is in her environment and can help her maintain her everyday functionality and also serve to reduce caregiver fatigue. The virtual human support agent can remind your grandmother to take her medications, or of appointments that she has upcoming, or that she needs to make a phone call, or that her favorite television show is coming up in 20 minutes.

But, in addition to all of that, the support agent could also be an engaging conversational companion. Imagine if programmed properly with personalized database access to your grandmother’s biographical history, photographs, family tree, etc., the support agent could engage your grandmother in what we call reminiscence therapy. That is where you try to keep the elderly person cognitively activated by stimulating old memories that are still well-preserved and well-accessible. The support could pull up photographs from your grandmother’s wedding day, or of her firstborn, or where she worked in 1952, or whatever—you know? These sorts of activities have been shown to promote well-being, but can be very taxing for caregivers to administer regularly.

In this way, it requires a convergence of a number of technologies—of course, the artificial intelligence, the virtual human development, the voice recognition, etc. But now you can create mixed reality applications that helps the specific user and keeps them company, plays checkers with them or some word game. It not only helps that person, but it also addresses the challenge of caregiver burnout, caregiver fatigue. Today, there’s a higher illness rate in caregivers, and their frequency of alcoholism and depression are higher. And in an aging global world, these mixed reality applications provide the opportunity to relieve some of that caregiver burden, while you’re providing direct benefits to the user.

How do you see mixed reality evolving?

Skip Rizzo: If past is prelude in any form, we can say that the technology is continuing to accelerate such that it’s now becoming more and more feasible to do applications in a research environment with increased probability of having widespread dissemination of this type of application, assuming the research supports its value.

There’s been a lot of work over the last 20 years in VR that has never escaped the lab. It’s unfortunate, because there’s really good research and really good application development in clinical tests with populations. But up until the last couple of years, the cost of the equipment to deliver this to the people that could benefit from it has been challenging.

Now we’re looking at opportunities where low-cost AR glasses will be the norm within four or five years. I believe that they will be embedded in our digital landscape at the same level as a mobile phone. We’re at a tipping point with the technology development. If you look at the functionality in today’s head-mounted displays at anywhere from $400-$800, it would have cost $20,000 a couple of years ago and not be as good. There’s certainly enough public enchantment and marketing potential to continue to drive investment in these technologies, and that will continue to evolve the technologies.

Eventually, these kinds of devices will be like a toaster—you know, you’ve got a toaster; every home has a toaster. You might not use it every day, but every home has one. And I think VR/AR and mixed reality devices will become commonplace in the digital landscape of people’s lives in the pretty near future—at least within the next five years.

With that said, I’ve noted lately some journalists taking the trendy “naysayer” role with VR/AR/MR. You know, the “VR is Dead” proclamations, kinda like the folks who said “Rock is Dead” a few decades back because it was a provocative thing to say! Well, rock certainly didn’t die after 1970, and I don’t see that happening now with VR/AR! While I get that there has been a lot of hype around these technologies, and sometimes the delivery doesn’t always match the expectations generated previously by some of the equally over-hyped tech writings we have also seen in the popular media. But the horse is out of the barn and the significant investment in “consumerizing” the technology has brought us to a point where there is no turning back. The disappointment in some of the lackluster sales numbers in terms of gaming and entertainment uses of VR/AR may be driving some of the dire predictions.

But in terms of healthcare, we already have nearly everything we need to add value over traditional methodologies—in fact, if all tech development in this area ceased tomorrow, we would still be at a level with the currently existing technology to do good work in clinical VR for at least the next 5 years or beyond. The tech has sufficiently caught up with the vision in these pro-social application areas, so if the techno pundits want to duke it out on the issues around the next big thing in gaming, then fair enough, but don’t think for a minute that we are not already at a real tipping point with the tech needed to support VR/AR use in the clinical domain!

What do you consider the role of IEEE to be in this space?

Skip Rizzo: I’m a member of IEEE, even though I’m a clinical psychologist. I’ve been working in the field for a long time, and I was part of the early days of the IEEE VR conference. I chaired it myself in 2003. I’m currently on the Mixed Reality Committee for the IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems. I’m a big believer in the IEEE mission—to foster technological innovation and excellence for the benefit of humanity. IEEE has always been visionary and vigorous, energetic, and supportive of getting the word out and fostering scientific advances in these areas. It’s a highly respected organization. I’m a fan.

Skip Rizzo will provide insight on this topic at the annual SXSW Conference, 9-18 March 2018 in Austin, Texas. The session, Clinical VR: Therapy with Potential & Power, is included in the IEEE Tech for Humanity Series at SXSW. For more information, please see http://techforhumanity.ieee.org.